Reading Ulysses

Touchstone. When a man’s versus cannot be understood, not a man’s good wit seconded with the forward child understanding, it strikes a man more dead than a great reckoning in a little room. Truly, I would the gods had made thee poetical.

Novelists of this present era are all too willing to sweep their metamorphosis under the rug. They prefer to think themselves born into this role which they were tasked with undertaking by no one. That metamorphosis, however, is ongoing, and the failures of the more fashionable creative outlets they entertained before the novel, whether it was the plastic arts, or performance, will surely crawl their way out from under that rug. A writer’s formation is overwhelming, painful if it is not done wisely, and endured wisely by few. For the would be novelist, novels may only be unique in that it takes years to write, whereas the other enterprises fizzled in months, if not weeks. The loved ones and close kin of the self-declared novelist lament the length of this latest creative death, until, if a lack of inspiration does not do it first, the isolation lays low the ambition and approves their better judgement. That wisdom, however sound, cannot well be heeded, because the novelist and the would be novelist share too many traits to easily discern which is which. Recklessness and irrational confidence are but two. A novelists’ better qualities, those of assiduity, and commitment, of the capacity for original conception, and, lastly, the realization of these in word, are only seeds, imperceptible at the outset, and always developing to a greater or lesser degree of malformation.

The erosion of the significance of the novel has coincided with the loss of our culture’s vitality. When a youth ruined with weary doldrums and an inexplicable ennui finds salve in a novel, finds they now have an idea of what is, if not wrong, then lacking, you have the makings of a dangerous thing. The onset of the writer’s psychological commitment must move through one touchstone or another, Ulysses mine. My purpose here is to show how a book incomprehensible to many, incomprehensible to many would be novelists, too, can catastrophically alter the course of an otherwise routine existence. In so doing, it may serve to soothe myself, if I can prove, against all likelihood, that the touchstone through which a writer moves can detect what qualities a novelist possessed when they commenced with a task that for me remains ongoing.

My scholarship will be lacking, but scholars are very droll characters, like enough to take no interest when meeting a writer, rather disdaining these encounters, in fact, lest they would actually need to talk to someone feigning to be of that distinguished stripe the scholar studies. Mine will be a personal testament, intended for reader of Ulysses approaching it without pretense, as is in keeping with my first reading of the book now before me, with entries about the course of my life throughout its margins. An alarming sincerity is discovered in rereading those entries, but they prove my point about metamorphosis and the rug.

Joyce is endowed with canonization because he put the confused elements of his day into an enduring form. Because these confusions were enumerated by Joyce with staggering entirety, there is cause for initial readers of Ulysses to scribe the moniker ‘difficult’ to the book. Although the word seems to confer agreement, there are as many striations in the use of that word, ‘difficult’, as there are baffled readers to harken it. In itself, the book produces more cause for conferral amongst its readers than amongst those that are put off by its first pages, or those, who having made it past those, ultimately find the scatology and deviancy grotesque. Ulysses’ readers discover a world worth revisiting, not only because it is intricate, but because those intricacies invite new insights, new perspectives.

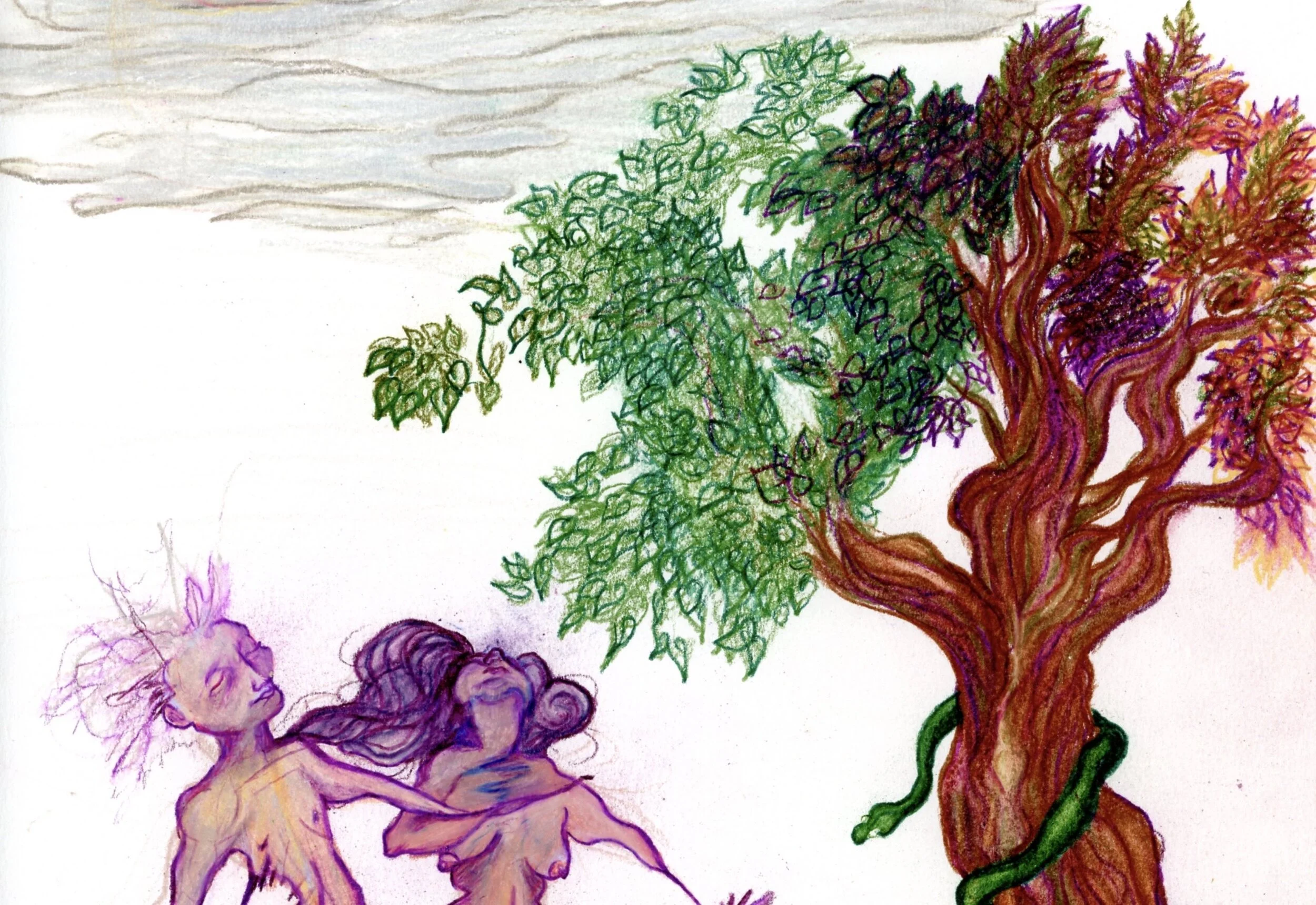

At the level of the sentence, Joyce is unrivaled. His creative marvels of verbal acuity are necessary equipment in the task of carrying off the arcana. These simplest and complex parameters, the sentences at one extreme and the arcana at the other, bookend the various equilibrium that manifest the character of consciousness and speed of thought, most exemplary made real in Bloom. This heart of things is where I seek the work. I look for how the inauspicious relates to man’s greatest marvels of thought. I look at the text’s inescapable constitution of Dublin, which Joyce took pains to ensure would be marred by nothing impossible, the Dublin of his book made real as the Dublin of the island, and see how the fidelity establishes the room for Homeric concordances to take root. The borders of conversations commenced in Dubliners unfolds in Ulysses to bring the humanity intrinsic to mankind, no less robust on barstools than in Aechean camps, to light. The equilibrium of the arcane and expressive create a portal leading form the inauspicious through to the most dire consequences of man within the context of Greek mythology. This Dublin and its Dubliners were familiar to me when I bought the book from a Barnes and Noble at 21. It also promised a kind of escape from the mundane, if though the mundane in itself could not be readily escaped. Replace Homer with Shakespeare, Aquinas, or Dante, and like comments would follow their names as followed Homer’s above. As is said about Dante, that The Divine Comedy represented a compendium of human knowledge up to that point, the same can be claimed about Ulysses. Because the book took shape, as Whitman’s cradle and axe arose, or Hart Crane’s bridge leaped, it allows us to weight the world of clatter, with that clatter communicated everywhere and all at once, in which we find ourselves yearning for Nostos.